In 1959 I was 8 years old. Though I did not know it at the time, soon the library in which I sat would be torn down, to be replaced by a gas station. All the books would be moved to a larger, more contemporary building of lower ceilings and better light; a building that has since been replaced by a newer building of even less character than the second. It amazes me how these bodies of flesh and bone we inhabit, these bodies that pump blood, bruise, heal, and sometimes hold their injuries hidden for years, outlast the brick and mortar that seem so much less flexible and, to the touch, appear convincingly more permanent than ourselves.

The red brick Canal building I sat in was situated upon the featureless flatlands of corn and soybean fields of West Central Ohio. Being only 8, my horizons stretched only so far as the nearest tree line a mile or two away. With my feet dangling a foot off the floor, I sat in a large leather chair studying the book that lay in front of me. It was one of the “Metropolitan” volumes on art history. With its oversize plates and sheets of velum paper between each page, it was itself a Masterpiece. Its sheer weight was awe inspiring. For my first few visits, during which I always returned to the same book, the librarian kept upon me a watchful eye, advising me how to carefully turn its pages.

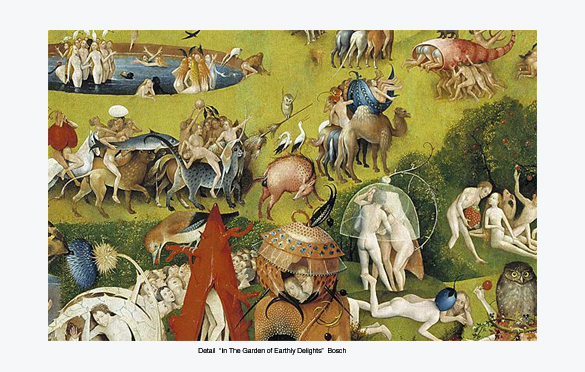

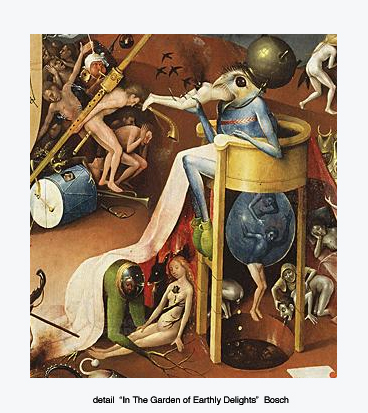

The first time I lay eyes on Hieronymous Bosch’s In The Garden of Earthly Delights, with its gorgeously rendered figures and unique and terrifying vision of hell, I looked about surreptitiously as if I had stumbled upon some forbidden secret, some pornography not intended for a child’s eyes. Once I realized that no one would stop me from looking, I poured over this image like no other. It entered my subconscious and soon began to emerge in dreams and visions. That a man could imagine and realize such a detailed and frightening subterranean world seemed to make the possibility of that world a reality. I knew, even then, this painting spoke of a place that exists beneath the surface of the physical world. It brought to life that world. In doing so, it has become, for me, the world’s most subversive painting, for it taught me to search beneath the surface, trust in dreams, and question practically everything.

Stan Berning